Key takeaways

- In 2022, markets have exhibited volatility and general weakness across the board, in part due to inflation and corresponding interest rate hikes. As a result, equity capital markets have had their slowest first six months since 2005.

- Despite the slow market, many biotech companies still need to raise capital to fund their pipelines and meet their next milestone.

- The need to raise capital in a depressed market has led to trends in alternative financing structures, some of which include private investments in public equity (PIPEs) and registered direct offerings (RDOs).

It’s not exactly a brilliant or unique insight to note for readers that the capital markets have been “¦ slow “¦ year to date. Perhaps glacial is more accurate. After a punishing first six months of the year, indices have shown recent liveliness in the back half of the summer during what is often a languid time of year for the capital markets. We have seen a slight uptick in traditional marketed follow-ons in the biotech sector. That said, the activity has been neither sustained nor permeated more broadly throughout the sector or across other verticals, and it would be premature to prognosticate what the balance of the year will look like for markets more widely.

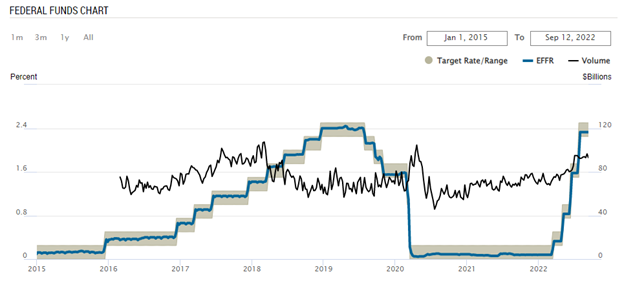

In the period following the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2007 to 2009, the Federal Reserve was able to encourage a remarkably stable and robust period in public markets through a mix of quantitative easing and interest rate management. There were certainly discrete slower periods and years, but generally, capital markets in the post-GFC world have been vigorous. The most jarring slowdown, in its swiftness and severity, was the micro-crash on the cusp of Q1 and Q2 2020, as the world reoriented itself around the COVID-19 pandemic. For six weeks, deals were iced and pencils dropped, and there was a tense moment where we all learned about the perils of astutely managing our virtual audio and video feeds.

To the rescue swooped the Fed, slashing the federal funds rate to zero – and the bonanza began.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York (https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/reference-rates/effr)

We were all witness to an explosion in activity in the new issue space, with traditional initial public offerings and follow-on offerings launching and closing at a startling pace. As the market stayed strong, issuers planned their follow-ons before the ink was dry on their IPO prospectuses. The first quarter of 2021 saw records broken in global equity capital market activity, with IPOs, secondary offerings and convertible notes offerings going on to break these newly set records just months later in the second quarter. Ultimately, 2021 set the all-time full-year record for IPOs and secondary offerings.

Source: Deal Point Data

As the world rang in 2022, rates were kept near zero, notwithstanding the consumer price index (CPI) pushing above 5%, 6% and (finally) 7% in November 2021. As the CPI teetered to an eye-watering 8.5% in March 2022, and inflation hawks were looking justified for the first time in decades, Jerome Powell’s Fed brought the party to a stop with meaningful hikes, first at 50 basis points (bps) in May and then 75 bps in June.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (https://www.bls.gov/cpi/)

A slowdown in new issue presaged the tightening, with a 67% drop in overall market total deal activity value year over year in the first half of 2022, the slowest first half in equity capital markets activity since 2005, according to Refinitiv. Year-to-date statistics have remained startlingly depressed, especially in light of the gangbuster 18 months that preceded the start of the year.

While the statistics suggest a generally listless market, they fail to tell a more nuanced story in the biotech space. Many biotech issuers were well-capitalized going into 2022, as a result of having hit the bid on financings throughout the boom in the back half of 2020 and 2021. But as companies burned cash to push forward trials and progress their vision, additional financing became necessary. In an effort to avoid dilutive financings, a number of issuers waited (and waited “¦ and waited “¦), hoping for more issuer-favorable valuations before (not always particularly willingly) entering the market using alternative structures to raise capital. In addition to issuers wrestling with depressed valuations, there are indications that generalist investors, who flocked to the biotech sector in recent years, have begun to pivot and look for alpha elsewhere, leaving the core cadre of long-term healthcare-focused funds, staffed with MDs and PhDs, evaluating strategic opportunities with a greater focus on the science.

Although there are green shoots of revival in biotech (depending on the day you check the market), many of the transactions that we’re seeing print have been defined by flipping the script from the boom times of 2020 and 2021 – instead of investors fighting for allocations in marketed deals, certain issuers are offering economic and structural incentives to investors to get them in the door and into order books. Depressed valuations across the sector have driven a shift in structure away from what became commonplace among many issuers over the years leading up to 2022 – the regular-way, common stock, marketed follow-on. A movement toward a greater flow of privately negotiated deals, in which issuers are selling more dilutive tranches of equity including warrant coverage, has become more common. While no two deals are alike, and the elements explored in this post are by no means universal across all issuers and investors, we have seen a number of structural and economic themes repeatedly presenting themselves in the current market, in large part stemming from the fact that an increasing number of deals are being privately negotiated.

Pricing

Transactions that aren’t publicly marketed bring with them the requirement to comply with stock exchange minimum price rules. For example, Nasdaq’s minimum price rules require that when an issuer is looking to sell more than 20% of its outstanding stock or voting power in a private offering, the issuer must seek shareholder approval or price a deal at-the-market (in extremely broad strokes; see footnote below).[1] Particularly in an environment of depressed valuations, companies are often seeking to exceed this 20% threshold in order to raise sufficient capital to reach their next milestone. These rules have required structured solutions to get investors requisite economics to participate in current choppy markets.

Warrants

One such structured solution is the inclusion of warrant coverage. Warrants have the potential to act as a good bridge between issuer and investor incentives, as they give the investor the right, but not the obligation, to purchase more of the issuer at a predetermined exercise price, which typically includes premium. Issuers avoid further dilution today, while investors are given the opportunity for more upside if the company has delivered and (presumably) experiences associated share price appreciation.

Ownership thresholds

Warrants (or preferred stock) can also serve to mechanically facilitate larger investments. Federal law obligates shareholders of a public company to comply with a panoply of requirements triggered at certain ownership thresholds (i.e., 5%, 10% and 20% of an issuer’s stock).[2] Such obligations include public disclosure requirements, but also potentially limit trading flexibility. To navigate these rules, many deals have come to include what the industry calls a “œblocker, ” whose sole purpose is to provide investors with the ability to increase their economic investment without tripping the relevant threshold. The blocker is often in the form of either a preferred equity security or a warrant whose exercise price has been prefunded by the investor. A blocker acts as a means to attenuate an investor’s ownership position, allowing the investor to disclaim the associated beneficial ownership.

Informational

While many transactions have been catalyzed by existing investors, new money often requests to do more diligence to better understand the story and, in particular, management’s planned use of proceeds and whether the proposed deployment of their capital will be accretive. Accordingly, we increasingly see deals with longer wall-cross windows and/or investors going under NDA to do more work and better understand the story. Additionally, there are even instances in which investors will do a deeper dive on the issuer and remain subject to confidentiality and market stand-off obligations following the announcement of the transaction.

To address the structural issues discussed above, we have seen a rise in private investments in public equity (PIPEs) and registered direct offerings (RDOs). While these structures are not novel, and companies have certainly leveraged these and similar deal types in years past, 2022 has brought a renewed interest in these alternative financing structures.

Private investment in public equity (PIPE)

PIPEs have seen a resurgence in recent months. A PIPE is a sale of equity or equity-linked securities to qualified institutional buyers and institutional accredited investors. A placement agent is generally hired to identify and wall-cross investors, but the deal documentation is papered as between the company and investor directly, unlike in a marketed, underwritten offering. The securities sold in the deal are unregistered and restricted, and therefore a registration rights agreement is executed when the deal signs, and in the months following settlement, the company puts up a resale registration statement covering the PIPE securities.

PIPEs don’t require an issuer to prepare a prospectus or other offering documents beyond off-the-shelf marketing materials that are generally freely available, making PIPEs relatively easy to prepare for. Additionally, the company never needs to publicly launch the offering, which carries with it the potential for embarrassing busted deals or very public undersubscription. Instead, a PIPE is fully executed prior to announcement. Finally, PIPEs have the potential to be more affordable for the working group from a legal and audit fee perspective, considering the lighter documentation and different liability standard for the placement agent.

Balancing these advantages, PIPEs can be challenging. On the pricing side, investors look for an illiquidity discount to account for the fact that their shares can’t be traded until registered on the back end, which discount is often expressed in terms of additional warrant coverage. These deals also have the potential to drag, as investors look to do more and deeper diligence when compared to the quicker and more streamlined traditional marketed follow-ons.

Registered direct offerings (RDOs)

RDOs have always been an option in issuers’ financing toolkits but have recently played a larger role. There are many similarities to the PIPE – these are nonpublic offerings in which investment banks are hired to wall-cross a select group of investors. RDOs remove the illiquidity discount discussed above, because the issuer is selling fully registered shares out the gate instead of relying on a resale registration statement on the back end. Regardless of whether non-underwritten or underwritten, investment banks should be comfortable with assuming “œunderwriter liability, ” in connection with these transactions. RDOs take two primary forms, as outlined below.

Non-underwritten RDOs

In non-underwritten RDOs, the issuer sells the securities directly to the investor in a share purchase agreement (SPA), just as in a PIPE. The primary differentiating factor relative to a PIPE is that the securities are sold pursuant to an effective registration statement, meaning that they are unrestricted and freely tradable out of the gate.

As a result, an RDO is conducted as a fully documented deal – a prospectus supplement, comfort letters and 10b-5 letters from multiple law firms all have the potential to increase legal and auditor costs, as compared to the relatively leaner PIPE. The RDO also requires having an effective registration statement or the ability to a file an automatically effective registration statement (i.e., be a well-known, seasoned issuer).

Underwritten RDOs

The primary difference between an underwritten and non-underwritten RDO is that the shares in an underwritten offering will settle through the banking syndicate instead of directly with third-party investors. The deal is marketed and conducted just like a non-underwritten RDO, with the banks wall-crossing investors and the shares being taken down off an effective S-3 shelf. But instead of the company contracting directly with investors through an SPA, the deal is papered on an underwriting agreement, with the banks purchasing the share block and settling onwards to their accounts.

[1] This is a gross oversimplification, as determination of the 20% threshold can be nuanced and is not always intuitive. Further, Nasdaq defines “œminimum price ” as the lower of: (i) the closing price (as reflected on Nasdaq.com), or (ii) the average closing price of the common stock (as reflected on Nasdaq.com) for the five trading days immediately preceding the signing of the binding agreement. This also doesn’t capture the implications warrant coverage has on the calculus, which need to be accounted for by adding 12.5 cents (presuming 100% warrant coverage on the deal). In short, the rules can be complex and require careful parsing to confirm compliance.

[2] Note that the means of calculating both the numerator (investor ownership stake) and denominator (issuer shares outstanding) can be complex and unintuitive and can change across different circumstances.

Contributors